During our recent trip to Chiang Mai, we spent one morning visiting the Thai Silk Village and Shinawatra Thai Silk. Thai Silk Village has been in the silk business for 20 years while Shinawatra has been around for 100. Thailand’s current prime minister, Yingluck, and her brother, Taksin, a previous prime minister, both come from the Shinawatra family.

The Chinese began making silk over 5,000 years ago. The silk is spun from the cocoons of the silk moth (Bombyx mori) that was domesticated from the wild silk moth (Bombyx mandarina). What domestication means for a silk moth is that the moth cannot fly, which makes it easy to raise and breed, and it has been bred to produce more eggs and larger cocoons.

The process begins with the female moth laying 200 to 500 eggs that each turn into a very tiny silkworm. These small silkworms — caterpillars, actually — feed continuously on chopped up mulberry leaves for three or four days before their first molting. Basically, the silkworm grows but its skin does not. When the silkworm outgrows its skin, it stops eating and then sheds its skin.

The silkworm molts four times, typically every three to four days. After the second molting, the silkworm can eat mulberry leaves without having to have them shredded first. After the fourth and final molting, the silkworm eats for seven or eight days and its body turns yellow. Once it stops eating, it looks for a nesting place in which it can spin its cocoon. It takes nine to ten days for the caterpillar to construct its cocoon.

So far, the silkworm has had a pretty easy life eating, molting, and spinning. Its fate, however, changes quickly since silk can only be extracted from the cocoon before the silk moth emerges. When the moth begins to emerge from the cocoon, its releases an enzyme that makes a hole in the cocoon. This hole breaks the long, continuous filament that the caterpillar used to construct the cocoon and hence the silk cannot be collected. Thus, the end is nigh, and for the pupa this means a deadly bath in water that is between 160 and 190 degrees so that it never emerges as a silk moth.

To my way of thinking, this is not the end of the silkworm’s life cycle but rather the pinnacle of it. If this warm bath were not in its future, the silkworm never would have been bred, born, or feed. This seems to me to be very much like domestic cattle whose real purpose in life, or more precisely in death, is to provide mankind with rib-eye steaks (medium rare, please!)

The silkworm’s cocoon is made of two main proteins — sericin and fibroin. Fibroin is the structural silk while sericin is the sticky material that surrounds it and that keeps the cocoon intact. The hot water not only kills the pupa but also softens the sericin so that the silk filaments can be spun. Each cocoon will yield between 500 to over 1,000 meters of silk filament.

After the raw silk is collected from the cocoons, it is quite stiff since it still contains most of the sericin. Repeated washings soften the silk by removing more and more of the sericin. As can be seen in the picture above, raw Thai silk is yellow. (In China and Japan, the silkworms have been bred to produce white silk). Before it can be colored, the washed silk is first bleached using hydrogen peroxide.

While some silk producers now use chemical dyes, the two that we visited use only natural dyes. These dyes are made from bark, roots, seeds, flowers, fruits, and leaves of plants and trees as well as from insect resin. These materials are mixed, boiled, and fermented to produce the desired color. Onion skins are used to make orange dyes. Insect resins, ash, and tamarind water create reds and pinks. Wood shavings from the jackfruit tree are used for yellows and mango tree bark is used for browns. Leaves and shoots from indigo plants are used for blue.

The silk threads go through several cycles of dyeing and drying in order to achieve the right shade and intensity. During the dyeing process, the silk is put in vats of hot dye and stirred constantly to ensure a uniform color. Once the desired color is achieved, the thread is washed, stretched, and put through a final dyeing process. When dry, the thread is wound onto spools so that fabric can be woven from it.

We saw several women working manual looms when we visited Thai Silk Village. They were weaving solid color fabrics as well as striped fabrics. Each weaver produces about 10-12 feet of fabric daily.

The stripes in the fabric can run either horizontally (across the loom) or vertically or both. To make the vertical stripes, different color threads are stretched lengthwise on the loom (these are called the warp). To make horizontal stripes (see the two pictures directly below), the weaver needs to switch between multiple bobbins that have different color threads in them. She needs to keep count of how many times she has used each color in what is called the weft so that the desired pattern is produced. A weaver can also alternate between smooth and rough silk to produce a physical stripe in the material.

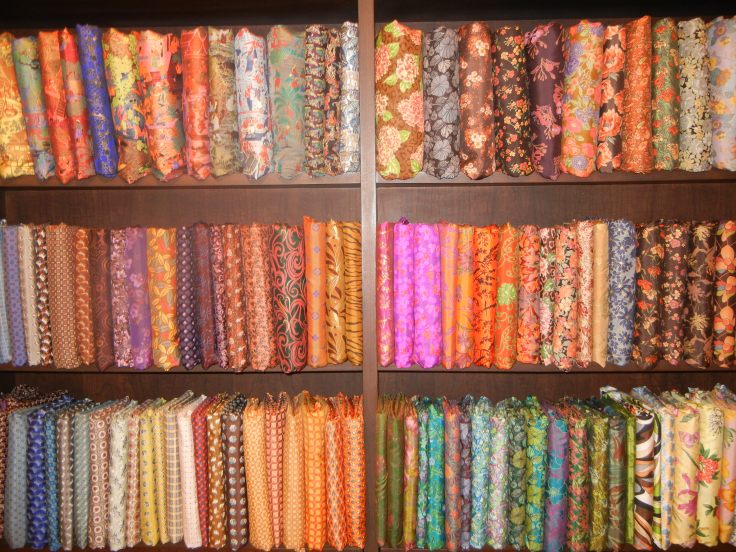

Lightweight, single-ply fabrics, from which scarves, shirts or blouses are sewn, are made using a single weft. Two-ply fabrics, suitable for jackets and heavier clothing, use a double weft. Even hardier four-ply fabrics, which are used for furniture upholstery or men’s suits, require four wefts. Designs can be printed on the finished cloth.

The final materials are stunning in their color, luster, and texture, and we seem to be acquiring an ever-increasing array of silk goods.

Kop Khun Krab!

Khun Kurt

Copyright © 2011-19 Kurt Brown. All rights reserved.

Whilst reading this, I kept thinking….Steve Yzerman, Steve Yzerman.

(Kurt Brown. All rights reserved)?